‚ÄúSounds like a trap. Is it a trap?‚ÄĚ says the shifty blue iris of Sophia Al-Maria‚Äôs ‚ÄėTsagaglalal (She Who Watches)‚Äô (2014) video. The robotized voice carries through the speakers of a CRT TV set, on rack and rollers, powered by a battery and pulled along by two straight-faced attendants wearing sunglasses. They‚Äôre the props for a guided tour of Frieze London 2014, commissioned by the fair, inspired by John Carpenter and starting at the pavilion‚Äôs tours and catalogues desk. It‚Äôs raining outside, the tent roof is being buffeted by strong winds and everything feels futile. ‚ÄúWill they withstand a real rain?‚ÄĚ Al-Maria‚Äôs words come less as a question than a warning as she interrogates the ‚Äútemporary structures‚ÄĚ of ‚Äúweak shelters covered in a carpet chosen to match the drapes‚ÄĚ that is the Frieze fair. It‚Äôs the premiere four-day event, bringing both the rich and the desperate from around the world to binge on ‚Äúthat great flower of our species‚Äô effort‚ÄĚ that some call art but Al-Maria‚Äôs omniscient eye calls commodity.

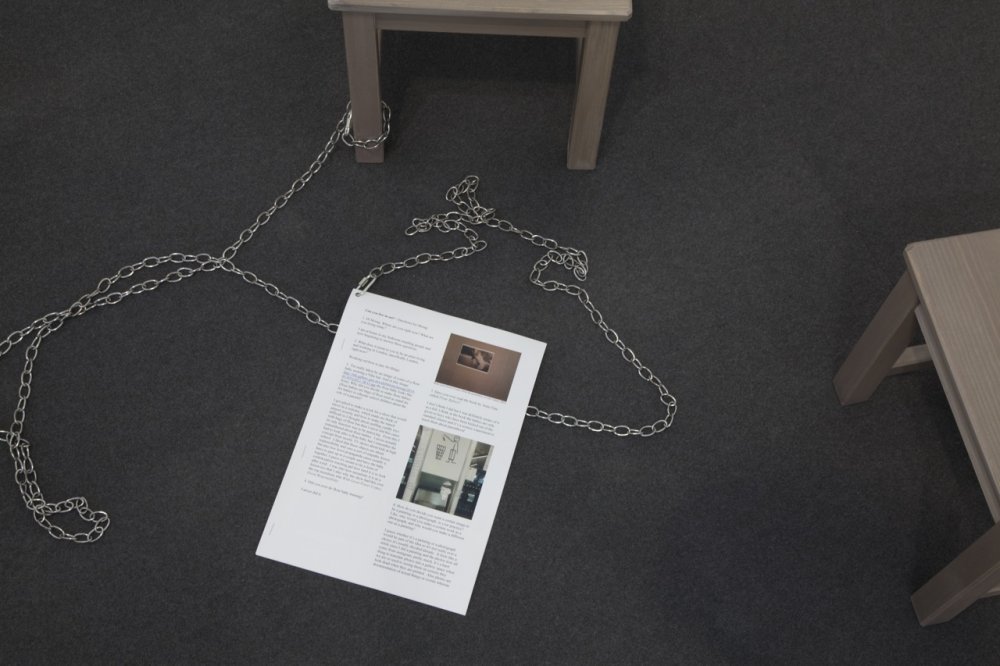

The TV and its two attendants lead their audience through a half-hour assault of the sections marked yellow, green and purple on the map in the Frieze Fair Guide. They’re the ones where each gallery‚Äôs share of the space appears to shrink according to their capital importance. Experimenter Kolkata and Project88 are there. The former features Indian art collective CAMP‚Äôs collaborative film ‚ÄėFrom Gulf to Gulf‚Äô (2013), while my Nokia won’t wordpredict ‚ÄėMumbai‚Äô when I try to type in the origins of the latter. Around here are the Gs, Hs and Js of the ‚ÄėFocus‚Äô of the fair, the smaller spaces with fewer viewers where the more interesting artists are. Morag Keil capitalises the letters spelling ‚ÄúREVENGE‚ÄĚ painted in acrylic across cereal boxes on a shelf in the center of an otherwise sparsely furnished Real Fine Arts booth. There are stuffed toys on one side; a conch, a hot dog and a puffed oat on a mixed media mount on the other. A print of an interview with Harry Burke called ‚ÄėCan you live in art?‚Äô is chained to a pair of chairs for children in a corner. It was originally conducted for Keil‚Äôs exhibition called L.I.B.E.R.T.Y..

Dreams.

‚ÄúIn a way, that‚Äôs what locations are today, different markets,‚ÄĚ says Michael Connor, moderator of the three-day offsite discussion series centred around its thematic title, Do You Follow? Art in Circulation. The stage is set up in the industrial space of the Old Selfridges Hotel, an extension of the high-end shopping centre. The infrastructure inside is non-existent so there are port-a-potties downstairs and the salon where the complimentary beer and Smartwater flows freely is full of plants framed by the building‚Äôs concrete structure. The sense of a space catering to the bottom feeding art marked ‚Äėpost-internet‚Äô couldn‚Äôt be better realised.

On Day One Martine Syms, Kari Altmann and token abstract expressionism expert Alex Bacon talk the #same-ness of networked art across aesthetics and algorithms. Takeshi Shiomitsu reads out his dense ‚ÄėNotes on Standardization‚Äô: and cites a subject position ‚Äď across race, gender, class, sexuality ‚Äď as shaping an experience of culture, while ‚Äúour interactions are rendered within the confines of the user interface or platform‚ÄĚ. Hence, the notion of dissidence-so-long-as-you-follow-the-rules, which is exemplified IRL when a puppy enters the building to the joy of the ICA staff but the chagrin of Selfridge‚Äôs security who force the dog and the human it‚Äôs attached to back outside.

It‚Äôs this fruitless performance of disruption that is probably best realised on Day Two during Constant Dullaart‚Äôs ‚ÄėRave Lecture‚Äô, his ‘BRIC mix’ booming across from a concrete corner as an art audience stands around largely unmoving behind obstructive grey pillars. They‚Äôre reading the geopolitical messages that dance in lurid neon streams of colour, the laser beams ‚Äúprojecting chemically enhanced pleasure into your children‚Äôs future‚ÄĚ. The sonic intensity of thumping electronica featuring languages I don‚Äôt understand generates that familiar feeling of fear and fascination that‚Äôs also at the core of Al-Maria‚Äôs ‚Äúcosmic horror of reality‚ÄĚ back at the Frieze pavilion. Tsagaglalal‚Äôs shaming gaze glitches, cuts and scrambles across fleeting interjections of images and bold white text: ‚ÄúEARTH LOST 50% OF WILDLIFE IN 40 YRS‚ÄĚ. Her human flunkeys run their UV torchlights along the pavilion walls to reveal the residue of human handprints glowing alien-blue.

How diverse. How pointless. These are thoughts that linger as the tour passes through this battlefield of economic warfare ‚Äď assaulted by art and artists fighting for attention. There‚Äôs the queer crosshatch of space, time and cultural signifiers in a lurid installation of Sol Calero‚Äôs ‚Äúciber caf√©‚ÄĚ at Laura Bartlett. PC computers propped on desks, among Hispanic food brands and gaudy gestural prints, are running on Windows XP and screening films of street parties. Men in dark blue overalls are chanting ‚Äúat the rodeo I was like, this is the one‚ÄĚ for Adam Linder‚Äôs performance art-for-hire at Silberkuppe. A line of people connected at the head by pink fabric walk past as part of James Lee Byars‚Äô ‚ÄėTen in a Hat‚Äô (1968) at the exact moment that Tsagaglalal asks, ‚ÄúWhat are these weird wandering ghosts?‚ÄĚ No joke.

‚Äú‚Ķthen we went to the ICA for a little bit, then we went to see Big Ben and the London Eye‚Ķ‚ÄĚ yawns a visiting invigilator at one booth describing a week of costly cultural enrichment before I‚Äôm confronted by Nina Beier‚Äôs ‚ÄėHot Muscle Mortality Power Pattern‚Äô (2014) at Croy Nielsen. Keychains and dog treats, power sockets and perfume bottles are embedded in packing foam and framed behind UV security glass above a carpet scattered with organic vegetables, ordered online for Beier‚Äôs ‚ÄėScheme‚Äô (2014). Villa Design Group‚Äôs live auditions for a film adaptation of Jean Roy√®re‚Äôs 1974 memoirs, ‚ÄėArab Living and Loving as Seen by a French Interior Decorator‚Äô at Mathew Gallery is filmed and re-mediated above the scene via a line of screens on the scaffolding. Carlos/Ishikawa offers free manicures care of Ed Fornieles over an Oscar Murrilo table flanked by Korakrit Arunanondchai‚Äôs body-paintings. ‚ÄėAffordable‚Äô limited edition reproductions by Parker Ito, Ne√Įl Beloufa, Ed Atkins are available for purchase at Allied Editions, while Richard Sides‚Äô mixed-media contribution warns ‚ÄėGamble Responsibly‚Äô.

‚ÄúThere‚Äôs even a food court‚ÄĚ is another observation of art fair infrastructure by Al-Maria‚Äôs Tsagaglalal that runs through my mind while watching a photographer take a picture of the ‚ÄúA to B Coffee‚ÄĚ caf√©. The people there are consuming across from the Corvi Mora booth, where Anne Collier‚Äôs framed C-print memo ‚ÄėQuestions (Relevance)‚Äô (2011) queries ‚ÄúWhat does all this mean?‚ÄĚ. An answer comes in the infantilised whisper of Laure Prouvost‚Äôs narrator in ‚ÄėParadise On Line‚Äô (2014), played in a pink-carpeted projection room at MOT International and suggesting ‚Äėgrandpa‚Äô is ‚Äújust interested in painting bottoms and not conceptual art‚ÄĚ.

‚ÄúDid I see Beyonc√©? Yeah, yeah, yeah‚Ķ‚ÄĚ an attendant groans through her phone, walking past Mike Kelley‚Äôs ‚ÄėRewrite‚Äô (1995) enamel on wood panel that reads ‚Äúour method of exploration: polymorphous perversity‚ÄĚ at Andrew Kreps. The thin metallic ‘clack’ of Hito Steyerl cracking a screen in her ‚ÄėSTRIKE‚Äô (2010) video is playing on loop at its entrance as it occurs to me that Beyonc√©‚Äôs presence was only felt at Frieze last year through the popular icon as self-image in Jonathan Horowitz‚Äôs eponymous mirror. It’s as if now the art and the image is not only reflecting a certain reality but somehow materialising it, in the same way that Amalia Ulman problematises the distinction between the performance and the person in her social media experiment in networked self-objectification, ‚ÄėExcellences & Perfections‚Äô (2014). Presented in a slideshow on Day Three of the Art in Circulation series, she reveals that the photos of her fake boobs were fake. The minor plastic surgery and talk with the ‚ÄėKing of Collagen‚Äô was real but the public breakdown wasn‚Äôt. Or was it?

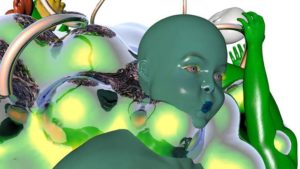

‚ÄúBodies are suitcases for a consciousness‚ÄĚ, announces Ulman, paraphrasing infamous body-modification pioneer Genesis P-Orridge, ‚Äúbut who is this suitcase by?‚ÄĚ In the case of the artist it‚Äôs one by the networked patriarchal gaze. Fellow panellist Derica Shields suggests an alternative model of authorship of the body for black women, reanimating themselves as cyborgs in 1990s music videos to create a ‚Äúsense of control but also invulnerability‚ÄĚ. Perhaps, it‚Äôs a way of achieving what Hannah Black‚Äôs polymorphous narrator can only aspire to while plummeting towards the earth‚Äôs core to the warped and slowed tune of Whitney Houston in ‘Fall’ (2014) screened before the panel begins: ‚ÄúAt 13,000 feet, I finally discover my own language‚ÄĚ.

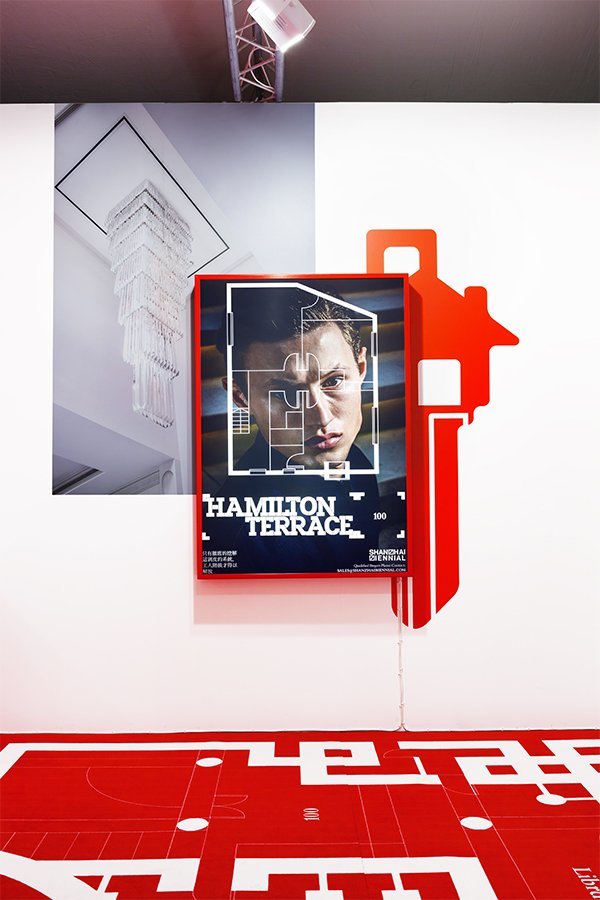

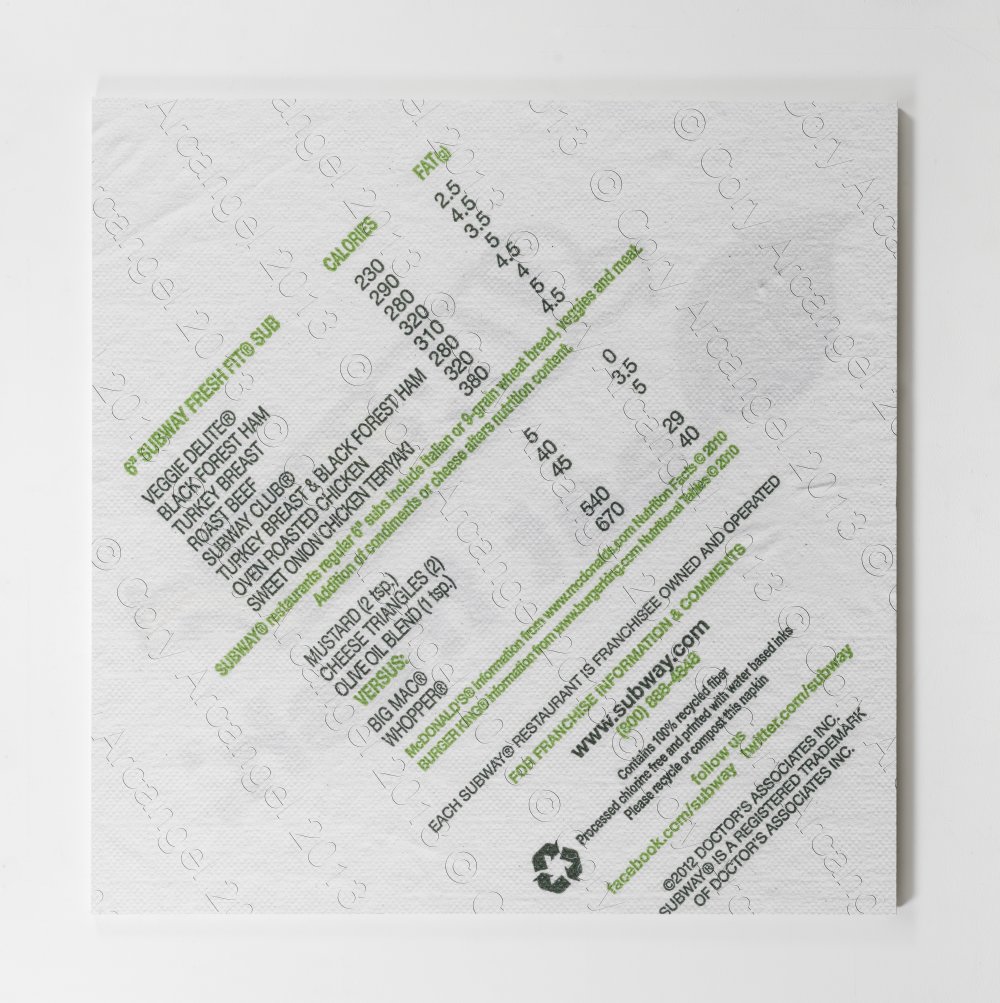

The search for language appears part of a perpetual capital exchange as pamphlets from Deutsche Bank encourage ‚Äú#artmagyourself‚ÄĚ; urging art viewers to ‚Äúpost a selfie with the artwork you love and win a terrific prize!‚ÄĚ whether it‚Äôs next to one of Cerith Wyn Evans‚Äô chandeliers or Heman Chong‚Äôs red vinyl text of ‚ÄėThe Forer Effect‚Äô (2008) that cold reads, ‚ÄúSome of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic‚ÄĚ. They‚Äôre as unrealistically aspirational as Shanzhai Biennial‚Äôs ‚ÄėLive‚Äô installation at the art fair entrance. There they re-imagine their work as real estate in the Frieze brand-emulating sale of a ¬£32,000,000 ‚ÄúUltra Prime Residential‚ÄĚ property in a room coloured rich-people-red with a contact email on the wall for ‚Äúqualified buyers‚ÄĚ only. Merlin Carpenter‚Äôs consciously crude painting of a middle-aged couple grinning in the golden glow of a stock sunset suggests ‚ÄėPrice on Request‚Äô at d√©pendance. Cory Arcangel‚Äôs Lakes series of flatscreen animations advances from ‚ÄėDiddy/Lakes‚Äô (2013) at the team gallery inc. booth in 2013 to the bigger Lisson Gallery. The ripples under ‘Miley Cyrus’ and ‘Dinner’ is powered by modems and hanging above the milieu of rainbow-coloured carpeting and Joyce Pensato‚Äôs huge black and familiar Disney head in ‚ÄėMickey for Micky‚Äô (2014).

The fabric of fantasy tears at one point when a cleaner walks past me in the Frieze pavilion‚Äôs ‚ÄėMain‚Äô section. She‚Äôs sweeping the space in front of Fiona Banner‚Äôs huge dark image of graphite on paper shouting ‚ÄúTHE HORROR! THE HORROR!‚ÄĚ in ‚ÄėThe Greatest Film Never Made (Mistah Kurtz – He Not Dead)‚Äô (2012). It‚Äôs an IRL occurrence that has a similar effect as Monira Al-Qadiri‚Äôs mediation in her ‚ÄėSoap‚Äô (2014) video. Screened at Art in Circulation and featuring popular Gulf soap operas based in worlds of affluence, Al Qadiri reimagines these shows that forever forget the labour behind the wealth by transposing the ‚Äėhelp‚Äô into existing episodes. A vase is smashed in a fit of passion. The maid bends down and cleans it.

‚ÄėBut what‚Äôs the plan?‚Äô one wonders as Christoper Kulendran Thomas explains his accelerated drive to bringing Sri Lankan artists into a post-fordist economy, whether they like it or not. The artist argues for an integration into the spread of malignant markets on the back of branded sportswear: ‚ÄúI was thinking that what failure for me would look like in this work, is probably what success would look like for a lot of artists‚ÄĚ. Though I‚Äôm not so convinced there‚Äôs that much of a distinction as I try to list every artist and booth who made it into Frieze worth mentioning: Simon Thompson at Cabinet London, Jack Lavender and Amanda Ross-Ho at The Approach, Lisa Holzer and Philip Timischl at Emanuel Layr, Hannah Weinberger‚Äôs ‘Frieze Sounds’ work, Soci√©t√©, Loretta Fahrenholz… There‚Äôs more but this whole piece has turned into an exercise in Search Engine Optimisation for ‘good art in a bad world’ while really just drowning in its own impotence as part of the fabric of collective failure.

‚ÄúIs this an art fair or a mall?‚ÄĚ barks Al-Maria‚Äôs electronic mouthpiece in my mind as I wander by Carsten H√∂ller‚Äôs ‚ÄėGartenkinder‚Äô playground at Gagosian and Salon 94‚Äôs acid-yellow curation of Snoopy animation and largescale emoticons causing retinal burn at ‘The Smile Museum’. This is definitely Al-Maria‚Äôs ‚Äúmaze of particleboard walls built to bare a heavy product‚ÄĚ. More succinctly, it‚Äôs Hannah Black‚Äôs ‚Äúshiny surface of a world of shit‚ÄĚ, as read from a poem performed during the Art in Circulation #3 talk, before speculating that ‚Äúhopefully we are the last, or among the last generations of a collapsing empire‚ÄĚ. Because when Monira Al-Qadiri says the purpose of the ‚Äúover-the-top, luxurious, crazy, dystopian image‚ÄĚ of the GCC art collective is to mirror the reality that ‚Äúour governments have somehow become corporations‚ÄĚ, it‚Äôs easy to assume that it also goes the other way. Along with the sense of being trapped in a violent cycle, circulated by the structures that exacerbate pre-existing socio-economic prejudice while hurtling us towards environmental collapse, one can‚Äôt help but agree when Tsagaglalal concludes, ‚Äúthis conversation can serve no purpose anymore. Goodbye‚ÄĚ. **